It makes sense to begin this column with a brief excerpt from Christopher Hitchens’s autobiography, Hitch-22. Attending a camp for young international socialists from around the world, Hitch was disenchanted when he found that the “camp” nomenclature was closer to the internment than the summer variety. Forgive the dramatics of opening up with someone else’s paragraph:

“I didn’t especially like the way uplifting music and hectoring speeches were played all the time on the camp’s loudspeaker system, but I was much more alarmed when, deciding on a hike one day to enjoy the surrounding scenery, I began to wave goodbye to the Cuban boys at the gate and was ordered to hold it right there. Where did I think I was going? On a hike. Well, I was told, I couldn’t. And why not? Because we say so… Once you have been told you can’t leave a place, its attractions may be many, but its charm will instantly be void.”

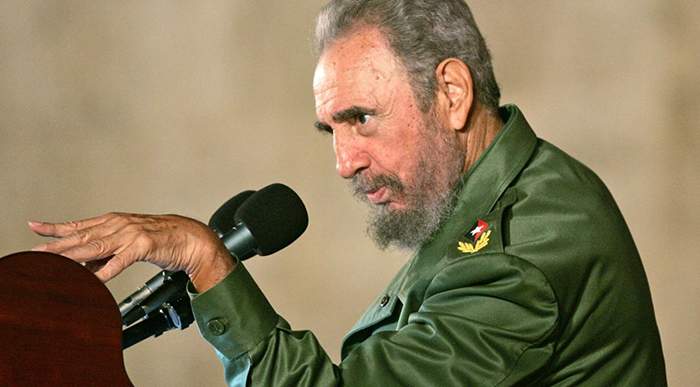

One thing that any observer of the media this week can be certain of is a fun park ride of cognitive dissonance over the death of Fidel Castro. There are those who have their opinions set firmly in mind—the refugees, immigrants and their children currently partying in the streets of Miami, for example, on one side of the spectrum, or the citizens of Third World nations who feel empowered by Castro’s legacy of focus on the poor on the other side—but there are many more who occupy the vast middle ground, the result of decades spent with coverage both vilifying and glorifying the revolutionary Cuban leader.

This middle ground is only going to grow more populated as many younger folks think seriously about Castro for the first time while reading the torrent of pieces about his death, and there’s something important to keep in mind as it does: Dictatorship, demagoguery, and the authoritarian impulse, whether born of the Left or the Right, are in and of themselves toxic and lead to the death of freedom, even if ancillary benefits exist or are plentiful.

Castro’s was a revolution that sought to empower the people of a long-abused and marginalized nation. It was that revolution that took the vastly disproportionate wealth of the country’s capitalists and did things like establish colleges on the grounds of their country clubs. It was this revolution, nearly alone among its Marxist-Leninist fellows, that did not massacre the bourgeoisie or descend into immediate and crippling violence. But it also led to a regime that claimed to have “abolished” both prostitution and homosexuality, that banned books and films, separated families, and treated its own citizens like so many bees in a hive—as state dictatorships are bound to do. It’s a system that, in 2010, Castro himself said, “Didn’t even work for Cubans anymore.”

The fact that such a regime can continue to exist is practically an advertisement for democracy. The mistake that can’t be made now is to see the word Socialism in print or on your screen and confuse it with leftist authoritarianism. Castro gave himself away early on with phrases like “Within the Revolution, everything goes; against the Revolution, nothing. Because the Revolution has its rights.” No matter where the person saying that falls on the Left-Right spectrum, such a sentiment is only a few steps away from, “Of course I’ll accept the results. If I win.”

![[Photos] HARD Summer Celebrated Its 10th Anniversary with a Barrage of Hip-Hop Heroes](https://merryjane.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/MJ_HSMF-2_SQUARE_Template.jpg)